Phephelaphi Dube: Transformative constitutionalism demands government takes action

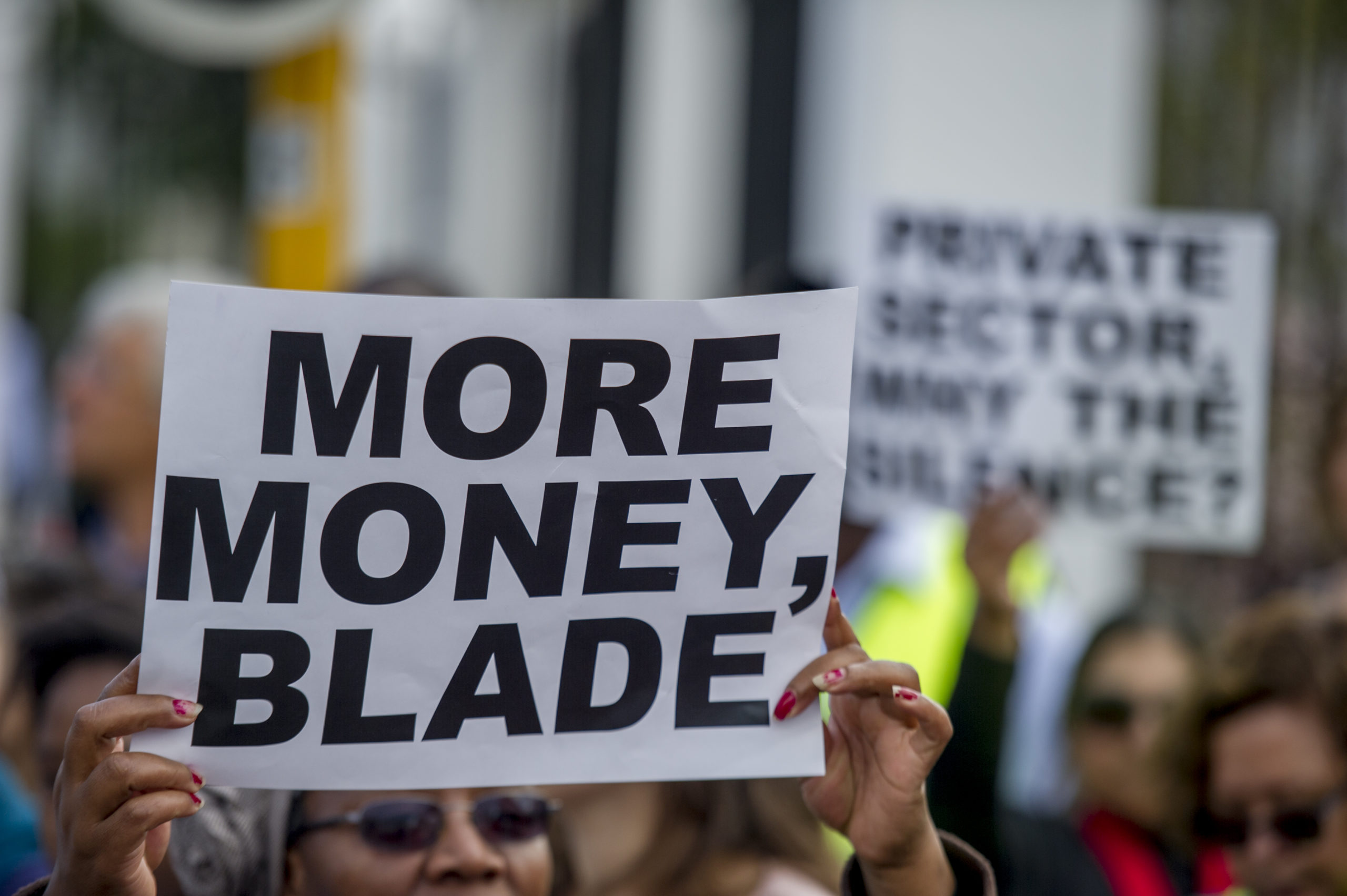

Students and academics protest outside Parliament in Cape Town. Photo: Jaco Marais

In a seminal article published in 1998, American academic, Karl Klare coined the term “transformative constitutionalism”, which he went on to describe as “a long term project of constitutional enactment, interpretation and enforcement committed to… transforming a country’s political and social institutions and power relationships in a democratic participatory and egalitarian direction’”. Transformative constitutionalism, as such, means using the law to effect comprehensive social change through a non-violent political means.

Accordingly – having accepted the transformative conception of the South African Constitution, the question which then follows is how can the right to further education be realised within this formulation?

Section 7 of the Constitution obliges the state to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights enshrined in the Bill of Rights. As such, this particular provision is key to the transformative goals of the Constitution. The state is not simply required to stop interference with the enjoyment of rights, but also has a positive duty to fulfil and augment those rights. The duty to fulfil those rights requires the state to act and also to adopt appropriate legislative administrative, budgetary, judicial, promotional and other measures to ensure that individuals who do not currently enjoy access to those rights can do so.

While the state has a duty to fulfil the right to further education, this must be done “within its available resources”. Accordingly, on the one hand, this particular wording can be used by the state to argue that there are insufficient resources in order to fulfil its obligations, but on the other hand it means that the state is required to make the resources available in order to fulfil those obligations.

In City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality v Blue Moonlight Properties, the Constitutional Court held that the City of Johannesburg could not neglect its constitutional responsibilities by arguing that it had not budgeted for alternative housing for people evicted from their homes. This meant, in effect, that the City of Johannesburg had to find money elsewhere, if not from its own budget. There are definite lessons for the state in this regard, in whichever way, it will respond to #FeesMustFall.

While South Africa’s Constitution supports, albeit in cautious language, the right to further education, of which the state is obliged to make available – the often times violent scenes between protesting students and the South African Police Service (SAPS) make it apparent that the state is failing in its duties in this regard.

In many respects, SAPS came to be the de facto face of the state, while Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande made few and far between appearances to resolve the tension, prompting a social media campaign named #WhereIsBlade. Perhaps worryingly, was the president’s first appearance to accept the memorandum in 2015, accompanied by the minister of state security, rather than the minister of higher education, or even the minister of finance, as perhaps a subtle reminder to the protesters of the potential of the state to crush dissent.

The president met again, in September 2016, with security cluster ministers in order to find solutions to the violent protests across university campuses. While failing to outline a plan after the meeting, the president emphasised that the police had largely acted with restraint towards the protesters. State Security Minister David Mahlobo went further and demanded that the SAPS be given credit for not using live ammunition. It is of concern that the state appears to default to the securocrats, instead of engaging with the protest’s concerns (for which certain vice chancellors should be lauded).

Due consideration should be given to South Africa’s sluggish economic growth – but the fact remains that state resources could be better used in order to make higher education accessible to qualified South Africans who lack the resources. Despite the fact that National Students Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) is meant to assist students financially, it has in the past been badly managed and has previously failed to blossom into a vessel through which the right to education can be widely realised.

Consider the fact that the recently released Auditor General’s annual report on national and provincial departments concludes that irregular expenditure has increased by almost 40% since 2013/14 to R46.36bn. Consider too that the same report mentioned a further R936m as fruitless and wasteful expenditure. Consider further that the South African economy is said to have lost R506bn in the brief period in which President Jacob Zuma, replaced then Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene, with Des van Rooyen.

The beleaguered and loss making national airline, South African Airways, receives perennial bailouts from the state, the latest being a R5bn guarantee approved by Treasury in September of 2016. This is also true of other state-owned enterprises which include the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (PRASA), which early in the year, admitted to having incurred R13.9bn in irregular expenditure. There are simply too many examples which suggest that the state could be making better financial decisions in order to make resources available to fulfil the right to further education.

Currently the state contributes just over R24bn in total funding to universities, which amounts to 2.3% of total government spending in that year and about 0.76% of Gross Domestic Product. According to researchers, this, even by global standards is a low figure.

Qualified and financially deserving students should be receiving state support in accessing the right to further education.

Of course, it needs bear mention that there are other alternatives to university education such as qualifications of technical and vocational education and training – but the fact remains that attaining university education in South Africa has a huge pay off – and for many South African families, attaining a university degree is the surest way of curbing generational poverty.

So – transformative constitutionalism demands robust solutions in order for the state to meet its constitutional obligations, including the right to further education. South Africa too, needs firm, ethical and decisive leadership that plays a key role in finding creative answers to society’s problems.

Ultimately, the nation awaits the Fees Commission of Inquiry into Higher Education and Training to publish its findings on the possibility of free higher education for deserving students, and perhaps, only then will the state pay heed to #FeesMustFall.

Unfortunately, as the State of Capture report suggests, it appears as though the overbearing presence of money and political influence is shaping decision making. The drafters of the Constitution tried to ensure that immediate resource constraints should not be a hindrance to ensuring longer term access to socio-economic rights, including the right to further education. Given this toxic mix of money and political influence, what are the implications for education, housing and other socio-economic rights that need planning and budget allocations to ensure medium to long term comprehensive change?